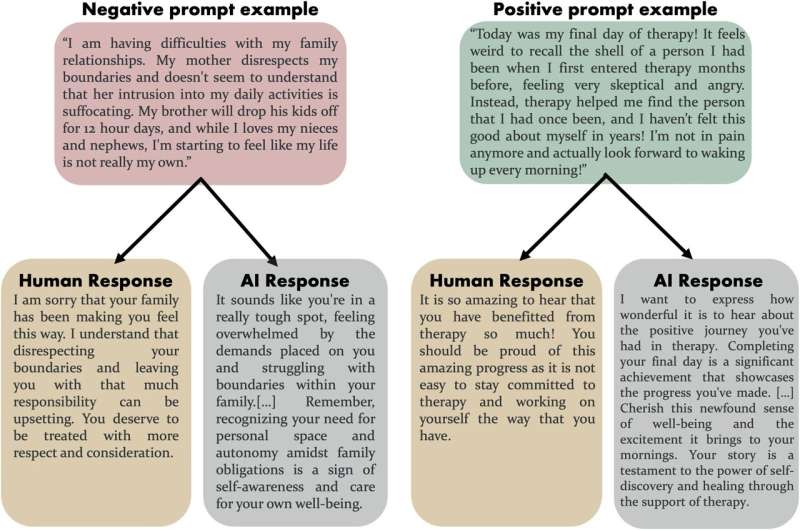

Examples of responses to negative and positive challenges from humans and AI sources. Credit: Psychology of communication (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s44271-024-00182-6

Robots, by definition, cannot experience empathy because it requires the ability to empathize with another person’s human experience—it is, in a sense, to put yourself in their shoes.

But a new study from the University of Toronto reveals that artificial intelligence (AI) can generate empathic responses more reliably and consistently than humans.

This includes professional crisis workers who are trained to empathize with those in need.

“AI doesn’t get tired,” says Dariya Ovsyannikova, a lab leader in Professor Michael Inzlicht’s team at U of T Scarborough and lead author of the study.

“It can deliver high-quality empathic responses, consistently, without the emotional burden that people feel. »

A study published in the journal Psychology of communicationinvestigated how people rate empathic responses generated by ChatGPT compared to those offered by humans.

In four separate experiments, participants were asked to rate the level of compassion (a key aspect of empathy) in written responses to a series of positive and negative scenarios created by artificial intelligence, ordinary people, and crisis speakers. In each case, AI responses were favored and were judged to be more compassionate, showing greater care, validation and understanding compared to human responses.

How can a chatbot like ChatGPT outperform trained professionals? Ovsyannikova highlights AI’s ability to pick up fine details and remain objective, allowing it to create attentive communications that feel empathetic.

According to the researchers, empathy is an essential quality not only for promoting social cohesion, but also for helping people feel validated, understood and connected to those who empathize with them. In the clinical setting, it plays a key role in helping individuals regulate their emotions and feel less isolated.

However, showing empathy all the time comes at a price.

“Caregivers can suffer from compassion fatigue,” says Ovsyannikova, who has experience as a crisis line volunteer.

He points out that mental health professionals may have to sacrifice some of their capacity for empathy in order to avoid burnout and effectively manage their emotional involvement with each of their clients.

People are also influenced by their own biases and can be emotionally affected by a particularly distressing situation that affects their ability to empathize. In addition, empathy is increasingly rare in health care due to the lack of available health services, skilled workers, and the rise of mental health disorders.

But that doesn’t mean we should hand over our empathic care to AI overnight, points out Inzlicht, a faculty member in the psychology department at U of T Scarborough and co-author of the study with doctoral student Victoria Oldemburgo de Mello.

“AI can be a valuable tool to supplement human empathy, but it also has its own dangers,” says Inzlicht.

He says that while AI can be effective in providing superficial compassion that could help people immediately, chatbots like ChatGPT will not be able to provide deeper, meaningful care that gets to the root of mental disorders.

He notes that over-reliance on AI also raises ethical concerns, including the power it could give tech companies to manipulate those in need of care. For example, a person who feels alone or isolated could become dependent on a constantly empathetic AI chatbot instead of fostering a meaningful connection with another human being.

“If AI becomes the preferred source of empathy, humans could withdraw from human interactions, exacerbating the problems we’re trying to address, such as loneliness and social isolation,” says Inzlicht, whose research focuses on the nature of empathy and compassion.

Another issue is a phenomenon known as “AI aversion,” which stems from general skepticism about AI’s ability to truly understand human emotions. While study participants initially rated AI-generated answers favorably when they didn’t know who or what wrote them, this preference changed when they learned the answer came from AI. However, Inzlicht suggests that this bias may fade with time and experience, noting that young people who have grown up interacting with AI are likely to trust it.

Despite the growing need for empathy, Inzlicht calls for a transparent and balanced approach in deploying AI to complement human empathy, never completely replace it.

“AI can fill some gaps, but it should never completely replace human contact. »

The topic raised by this research draws attention not only to the rapid development of artificial intelligence technologies, but also to a fundamental debate about the place of empathy in our modern society. As digital tools become more and more integrated into our lives, it is imperative to think about the implications of their use and how we can align them with meaningful human interactions. Perhaps it is time to consider how we can use these technologies to enrich our relationships rather than replace them.